The Irish government lacks in developing re-integration plans which other countries like the United Kingdom and Australia have efficiently developed. For example, the United Kingdom has a ‘desistance and disengagement programme’. This program aids and supports the issue that arises from radicalisation. It also includes an exhaustive plan for the re-integration of foreign fighters into society by providing them mentoring tools and psychological support. A similar strategy is also being adopted by countries like Germany and France. The reason behind adopting this approach is the understanding that disengagement from radicalisation can happen only through a copious understanding of the fighters’ circumstances and strategic steps to deal with it. The inclusive and participatory planning processes can also help to identify specific factors like in case Smith that are usually left unexplored but greatly contribute to the marginalization of women like her and hence in their contribution to radical violence.

References

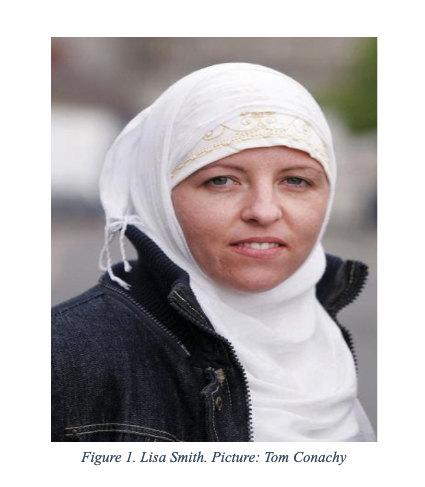

- BBC (2019). Islamic State bride: Who is Lisa Smith? BBC News. [online] 2 Dec. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50629420 [Accessed 20 Sep. 2021].

- Carswell, S. (n.d.). Lisa Smith’s detention extended as solicitor says she has “strong case.” [online] The Irish Times. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/crime-and-law/lisa-smith-s-detention-extended-as-solicitor-says-she-has-strong-case-1.4101773 [Accessed 20 Sep. 2021].

- ICCT (2016). The Foreign Fighters Phenomenon in the EU – Profiles, Threats & Policies. [online] Icct.nl. Available at: https://icct.nl/publication/report-the-foreign-fighters-phenomenon-in-the-eu-profiles-threats-policies/.

- Irish, I. (2019). Lisa Smith walked through “bombs, poverty and desert” to get back to Ireland, court told as she’s charged with Isis membership. [online] independent. Available at: https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/courts/lisa-smith-walked-through-bombs-poverty-and-desert-to-get-back-to-ireland-court-told-as-shes-charged-with-isis-membership-38753169.html [Accessed 20 Sep. 2021].

- Onishi, N. and Peltier, E. (2019). Turkey’s Deportations Force Europe to Face Its ISIS Militants. The New York Times. [online] 17 Nov. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/17/world/europe/turkey-isis-fighters-europe.html.

- RTE (2019). How was Lisa Smith radicalised? www.rte.ie. [online] Available at: https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2019/1112/1090249-how-was-lisa-smith-radicalised/ [Accessed 20 Sep. 2021].